An incomplete martial arts autobiography

They say it’s not the pedigree of the dog in the fight but the fight in the dog that’s important.

Regrettably, every time my name comes up in conversation it is nearly always associated with karate, which for me is like being referred to as a poodle rather than a pit bull. The truth is that out of over fifty years of practicing the martial, which includes being trained under my father from the age of eight and researching the martial arts of the East and West for over forty years, only eight of those years were spent practicing karate. I suppose in order to give karate some credibility as a fighting system, my fighting ability was often cited in magazines and conversations as to karate’s effectiveness; but even though I was wearing a gi for eight years, what was going on underneath it had nothing to do with karate and everything to do with my psychological state of mind, an innate athleticism, and the training and fighting I had engaged in since early childhood.

Early years

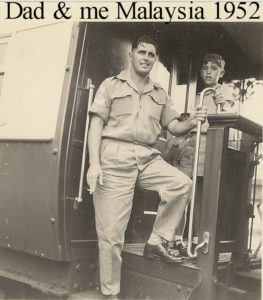

My father was nicknamed Tiger at the school of PT in Aldershot, not only, I suspect, for his ferocity when milling or bayonet training,but also for the way he moved (though prowled might seem a more appropriate term). As a member of the Army Physical Training Corps Tough Tactics Team, he earned a Mention in Dispatches for his work in preparing Gurka troops amongst others for jungle warfare and accompanying them on bandit patrols during the Malay bandit campaign of the early 1950s.

Not only did my father introduce me to milling, boxing, gymnastics, and how to negotiate an assault course and fire a 303 from an early age, but he also enabled me to witness demonstrations of kung fu first hand because he organized local Ipoh kung fu teams to demonstrate their skills and strength at sporting events. (I had already gained some familiarity with kung fu through my visits to the local Ipoh cinema from where I would emerge punching, kicking, and slashing and stabbing the air with my bicycle pump, much to the delight of the onlookers. Indeed, it was by watching a demonstration of Monkey Boxing that I first learned to stand on folded toes and eventually to run and perform bunny jumps on them).

My father was an elite athlete by anybody’s standards. Apart from being as strong as an ox, he could ride Roman style and jump hedges and ditches bareback; he was a prominent member (along with Nick Stuart) of the Army Physical Training Corps gymnastic team; he was News of the World cross-country champion, Northern England Badminton champion, and the captain of the British Army basketball team that came third in Brussels shortly after the Second World War (the Americans coming first and the Canadians second). He could fence, wrestle and box, and his team held the forced march record across the Yorkshire moors for several years. Indeed, I recall him recounting that when taking Gurkha troops on forced marches in Malaysia, he ‘knew he had them’ when they began to bite on pieces of rag they were carrying. To show the stamina of the man, he often did two forced marches a day with full kit. With such a father is it any wonder that so many so-called martial arts masters failed to impress?

My father had a wisdom of the body that superseded his academic knowledge of it, as well as awareness of those who were lacking in it. I remember after witnessing a demonstration of karate by the leading masters in the world, he turned to me and said, ‘Stephen, they can’t even walk and spit at the same time’—an expression he reserved for only those he considered to be physically inept (and to which the late Danny O’Connor added when I recounted the story, ‘Yeah, they just shuffle and dribble!’)

Kyokushin Kai

Long before I ever considered entering the Kyokushin Kai dojo of Bob Bolton and Steve Arneil in 1967 (from which I was expelled for rough play in 1968), I knew how to fight. I was also an athlete in my own right. On my very first night on the beginners course, Bob Bolton was amazed at what I could do, and I was immediately sent upstairs to train with the more experienced group. However, it was obvious to me and anybody else that was watching that my level of atheleticism surpassed theirs. As I said, I could fight, but my unofficial version of fighting—as taught to me by my father, picked up watching kung fu, practiced in scuffles whilst at boarding school in Germany and later in barrack rooms brawls and street fights whilst serving as a boy and regular soldier from 1958 to 1966, and supplemented by those moves that I had read about in books on boxing, wrestling, jiu-jutsu, judo and karate and that I had found to be effective on the streets—didn’t resemble by any stretch of the imagination the official Kyokushin Kai version of fighting as taught by Bolton and Arneil.

Though it was far more effective.

As a visitor one Saturday afternoon, I had broken someone’s arm with a front kick; whilst on my first official introduction to kumite (I think it was my second night) I decked a Swedish second dan with a vicious right cross, setting a precedent for things to come. In every competition I ever entered I was disqualified for excessive contact, including the one in Holland against Jon Bluming’s team. Growing tired of the game of tag my opponent was playing, I cornered him and kicked him straight in the groin/femoral artery with folded toes. He immediately passed out and went into shock with blood pouring from his nose. Fortunately for him and me, he later recovered. Every time there was kumite in the dojo there was a scrimmage in the line-up just to avoid pairing up with me, as there seldom was a time when somebody didn’t get injured, including the time I dumped a certain individual hard into the mat and—when he called me a ‘fucking bastard’ for doing so—promptly put a long, deep gash over his eye. He was immediately rushed to hospital and I was banned from the dojo and eventually expelled by Steve Arneil and his bunch of cronies from the Kyokushin Kai, reputedly the strongest style of karate in the world. No matter how many times I was disqualified or admonished for heavy contact, I simply couldn’t learn to miss.

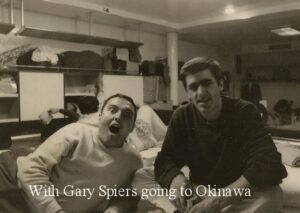

To me, a fight was a fight. Period. Missing wasn’t something I practiced or endorsed. The late Gary Spiers recalled amusingly in a magazine how I put a dent in a Japanese second dan’s forehead in the exact shape of my knuckles, which were the size of small eggs at the time, and I believe my old friend Dickie Wu was still experiencing considerable pain years after I hit him in the jaw. Although I deeply regret injuring some people, others I do not. When somebody came rushing in towards me, be he friend or foe, I simply couldn’t check the impulse to hit him before he hit me, and the harder the better. My father’s lessons of timing my shots at the precise moment the opponent was adjusting his position or shifting his weight towards me had, through repeated practice, become instinctive. It is therefore not surprising that if some screaming Banzai Billy came rushing in square on with his hands down, head up and mouth wide open, it was inevitable his face was going to collide with my fist.

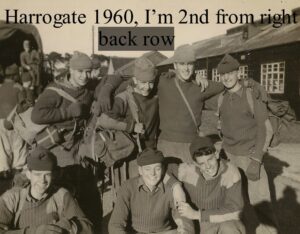

One such aspiring samurai once received a black eye, deviated septum and a chipped tooth, all from a single shot. Something else my father had taught me was to hit diagonally down like chopping wood with an axe, not only to increase the power but also to increase the likelihood of hitting more targets. I suppose I am someone who just loves the challenge of a real fight, irrespective of the superior size or reputation of my opponent. Even on the day of the previously mentioned incident that led to my expulsion, I had been sacked from Courage’s for head-butting and breaking the jaw of a fellow drayman far larger than myself and with a hard-man reputation. Indeed, the whole reason I joined the Kyokushin Kai in the first place is that following my dishonourable discharge from the Army in 1966 for not only my belligerent attitude towards NCOs and officers, but for persistently fighting in barracks and amongst the local populace of Harrogate, Catterick, Nairobi, Benghazi and Bampton (it was not unknown for me to have two or three separate fights in a day), I knew that if I didn’t get some positive direction to my aggressive, violent behavior it was going to be sooner rather than later that I would be serving serious time at Her Majesty’s pleasure. Somehow after reading Oyama’s first book I had managed to convince myself that karate would provide the challenge I was so desperately in search of. However, marching en masse up and down the dojo floor to nowhere to a regimented, barked-out command and engaging in overly restrictive ways of fighting was not the way of the warrior that I had envisaged.

Japan

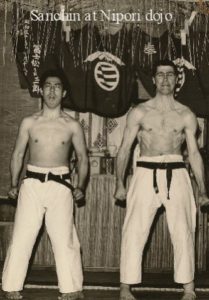

Desperate to still give some direction to my life after being expelled from the Kyokushin Kai, I travelled to the land of the samurai, where I immediately enrolled as a beginner at the Nipori dojo of Yamaguchi Gogen, ‘The Cat.’ However, it soon became clear to me that it was me that was pissing and shitting blood as a result of training never less than eight hours a day and seven days a week, sometimes not eating for days—not my fellow training partners. Nevertheless, I persisted in the hope that one day a real samurai would turn up, though one never did. In three months, much to Yamaguchi Goshi’s chagrin, I was awarded first dan by The Cat. (During the performance of the kata saifa as a result of my stamps I put two holes in the wooden floor and possibly even cracked the beam.)

Okinawa

Carrying a letter of introduction from Yamaguchi Gogen, I arrived at the Naha Dojo of Yagi Meitoku, tenth dan in Goju Ryu. Introduction complete, I was then allowed to watch the practice, which took place in a very small room—so small, in fact, that the performers had to continually adjust their steps to as to avoid running into the wall. Not that this was the only interesting aspect of the training, in that the performers moved in unison not to a senior’s command, but to a tape recording of Yagi’s undulating voice—the batteries of the small tape recorder must have been running out!

Promising I would return—I never did—I went in search of something better. After days of searching I finally ended up at the dojo of Miyazato Eiichi. However, at the time he was not accepting foreigners—or so he thought, in that after he refused me entry I remained outside of the front door to the dojo for several hours until he relented and let me in. Still the test wasn’t over, and he made me kneel for another hour or so at the entrance to the dojo. Then he ushered me in and made me sit in military fashion on a very narrow bench. At the closing of the dojo several hours later he allowed me to sit easy, a fee was negotiated and I was accepted as a student; again I enrolled as a white belt.

The next day as soon as Miyazato opened the dojo I was standing there. He smiled and then took me through the etiquette required of the dojo, then handed me over to a third dan who spoke good English. After watching what I could do, Miyazato disappeared into his office and emerged carrying a black belt, which he insisted I put on. I refused; he tried again, and again I refused. He laughed and went back into the office. Within no time I had all of the exercises with and without equipment, drills with a partner, and all of the forms, under my white belt, so to speak.

Most of the forms I knew anyway, and correcting them to satisfy Miyazato was no big deal. The other forms, including the 108, I picked up by watching others performing them or being taught them. This I did by first watching them and then, on the pretext of going to the toilet, going through the form in the large shower room, occasionally popping out to see where I had gone wrong. Ever since I can remember I have been able to accurately replay events within my mind’s eye, a faculty which has always allowed me to learn a move or series of moves very quickly.

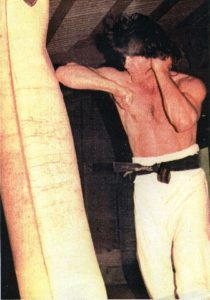

Free-fighting within the Miyazato dojo was nonexistent. Perhaps it would have spoilt the tranquility of the training, which was only ever interrupted by the slaps of someone being tested in Sanchin or the reverberating sound of someone punching the makiwara. Unlike in Japan, there was no marching en masse up and down the dojo floor. Training focused more upon the individual than the group.

Whilst I enjoyed my stay at the Miyazato dojo, it wasn’t without incident. I once took exception to being tested in Sanchin by one of Miyazato’s most senior grades, whose name escapes me. He was taking obvious delight in repeatedly slapping my back, knowing that I was suffering from severe sunburn at the time. It wasn’t so much the pain that got to me, but the idea he was getting so much pleasure from what he was doing. At the completion of the test I challenged him then and there. He refused, despite outweighing me by about four stone.

As in Japan, the training on Okinawa had no basis in reality. Equally, as I was later to find out through my research into the Fujian fighting traditions, the assurance that I was repeatedly given by Yagi and Miyazato that the training was performed ‘as in China,’ was an exaggeration. The resemblance was only superficial.

Fixing, Faking, and the Dojo Culture

Practice shouldn’t be done for its own sake, for the attainment of some noble spiritual goal, or for some sadistic or masochistic pleasure, but with fighting in mind—and the more realistic the fighting, the better. Some readers might ask, if I wanted realism, why didn’t I take up Muay Thai? I did, but when it came to my first match I was told by the promotor that if I wanted to get paid I would have to take a dive in the second round. I naturally declined and the match didn’t go ahead.

When in Japan not only did I discover that the samurai no longer exist, but that in one way or another most things are fixed. Grades are fixed if you have enough money and in particular if you are a foreigner. Breaking is fixed. According to Lloyd Williams, a corrrespondent for Black Belt magazine, even the first tournament of Oyama ‘God Hand’—in which to the audience’s delight Oyama failed on several tries to lop the top off one of several different bottles—was fixed. Williams relayed to both myself and Brian Fitkin who the winner and second and third place fighters would be and the reason why: they were going to open kickboxing dojos. Judging from many of the decisions, and in particular those made against the Thais, he could have been right.

Unlike all too many martial artists of the East and the West, I never had any difficulty in viewing the claims made by the masters or on their behalf with regards to their extraordinary powers and skills as being nothing more than bullshit. Despite the so-called evidence, stories of throttling tigers and killing bulls with bare hands are nothing more than ploys to draw the suckers in. I suppose if the masters concentrated more on becoming supernormal through realistic and effective training and fighting methods rather than, by some deceit or another, appearing to be superhuman, I would have found them to be more credible. I didn’t go to Japan in search of someone I could worship as a god but someone on a physical plane I could emulate as a fighting man.

Amongst many of the things I had great difficulty in coming to terms with whilst living and training in Japan was how on one hand I was expected to accept the superiority of the Japanese as a race, and on the other, as a foreigner, to also accept being treated like vermin. Of all my experiences in Japan the most distasteful was having to witness some junior who hadn’t the balls or the ability to fight back (or was reluctant to do so) accepting a beating administered by a senior as part of his initiation into dojo culture and etiquette, which essentially means that those on the bottom of the pyramidial dung-heap of rank and privilege must show subservient respect to those at the top.

Not that the seniors took such liberties with me, as they had seen what I could do when fighting second, third and fourth dans during my first grading. The idea that seriously injuring or humiliating someone contributes to their learning experience as a fighter is a nonsense, and such views are usually put forward by those who can’t fight, in that it’s the only way they ever get to beat somebody up. My Japanese and Okinawan experience from a combative perspective had been a complete waste of time. I’d had better fights during basketball, rugby and football matches with the opposing players, those of my own team, the referee, linesmen, and spectators than I had in Japan!

Though disillusioned with karate and those other martial arts I had witnessed in Japan and Okinawa, I still felt obliged to honour my agreement with George Chew, co-founder (with Eric Dominy) of the London Judo Society, who had helped me enter Japan on a Judo scholarship under the sponsorship of Mr Hatta of the Japanese Diet, Mr Aoki of the Benihana restaurant chain, and Professor Watanabe of Waseda University. I had agreed to take up the position of resident instructor of the karate section on my return to the UK, the post having been previously held by Steve Arneil. I had also agreed to a fee which far exceeded the £15 per week offered me by Chew, a weekly wage that, as it would later emerge, had been taken by Chew from the money collected by students to help with my stay in Japan, and which Chew had failed to forward on to me.

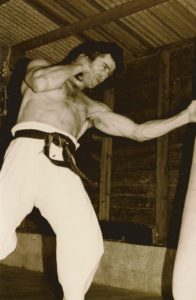

Unaware that Chew had fleeced the students as well as me, I began a Spartan regime of training that reduced the membership of over two hundred, to three. Chew, either because the collection money had run out or he began to suspect that it was me punching and kicking holes in his walls and ripping doors off their hinges and destroying the makiwaras, gave me the sack.

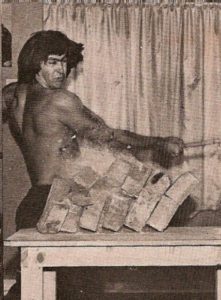

Building sites, barracks and boxers

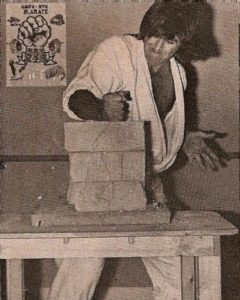

My obligation to Chew complete, together with my disillusionment with the martial arts establishment, I returned to working as a hod carrier on the building sites around Reading. At one such site, stripped to the waist, I once gave an impromptu display of brick-breaking to a group of office girls gathered at a window overlooking the building site. However, my display was interrupted by a co-worker, a journeyman professional boxer who effectively asked me if I could do the same to a man, to which I replied, ‘Let’s find out.’

So we retired to the top of the building and no sooner had the proceedings begun than I secured a hold on his head as he attempted to bob and weave in towards me and put two vicious knees into his face. He immediately collapsed in a heap with blood pouring from a broken nose. It later transpired he also had a fractured cheek bone.

Not that he was the first professional boxer I’d fought, the first being when I was a boy soldier at Harrogate. During a PT lesson the assistant instructor, a professional boxer doing his national service, organized a last-man-standing milling contest, something which by way of my father I was all too familiar with. It resulted in me dispatching two of his camp boxers and hospitalizing a third with double vision. The proceedings having been brought to an immediate close, I was then marched into the office of the SMI (Sergeant Major Instructor) and given a bollocking for hitting with the open glove. The SMI then asked me out of the blue if I was the son of Steve Morris. I said yes and he said, ‘Oh, well that explains it,’ and I was marched out of the office again.

Somehow anticipating what would happen at the next PT lesson, I was not surprised when the assistant instructor turned to me and suggested we put on the gloves. Though I doubt if he ever anticipated what would happen next. Needless to say, PT was never quite the same after that; indeed, I often didn’t even bother to turn up. At only 15 this incident was a defining moment for me. Indeed it has been the fights in my life that have often defined me, including the one I had with Ian Buckley, at the time my best friend, but by the end of the fight, my worst enemy. The fight, which started out as a minor argument shortly before we were due to go to a trade class, then went on to develop into a major battle that lasted over an hour and would have gone on longer if we hadn’t been dragged apart by other boys returning from class. Each battered and bleeding and in a state of near total exhaustion and with our differences still unresolved, we didn’t speak to each other for nearly two years.

Much has been made of Helio Gracie’s legendary battles, but the truth is men (and boys, as it was in our case) have been engaging in similar battles for domination for many hundreds of thousands of years; it is not something peculiar to a race, individual or system.

The second boxer I ever fought, though in truth he wasn’t a professional boxer but an ex-Army heavyweight boxing champion who was planning on going professional when he left the Army, was at Bampton. Knowing my reputation, this individual baited me whenever the opportunity arose. Having seen him at work and because he outweighed me by about three stone, it was the only time I ever hesitated in taking up a challenge. But the evening he provoked me in the TV room turned out to be his biggest mistake. Instead of attempting to take him there and then, I left the TV room with his laughter still ringing in my ears, went to my barrack room, cleaned my locker, changed my underwear and socks and then lay down on my bed staring at the ceiling and replaying in my mind’s eye what I was going to do to him. Highly aroused, I returned to the TV room, where it must have been obvious to everybody what was going to happen next, because the TV room cleared in a matter of seconds, leaving only the two of us facing each other.

Not giving him time to set up, I then proceeded to butt, punch and quite literally kick the shit out of him, leaving him lying unconscious in a pool of blood and his own stench.

Returning to my barrack room, I cleaned up and began preparing my kit, as I had often done before, in anticipation of the early arrival of the Military Police. However, they didn’t turn up. Curious to find out what was going on, I eventually found my former adversary completely incoherent in the washroom being cleaned up by his mates before being taken to hospital where he remained for a week.

Funny enough, the Company Sergeant Major later that evening pulled me aside and instead of putting me under close arrest, unofficially congratulated me. It seems I wasn’t the only one this individual had pissed off. Nothing ever came of the incident, as apparently his story was that he had been beaten up whilst down in the town. Not that it really mattered as I was discharged from the Army two weeks later, aged 23.

High sensation seeking behaviour and Catterick Military Hospital

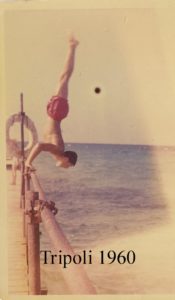

My life has been full of extremely violent incidents. Undoubtedly this pattern was not only influenced by my genetics and life circumstances, but also by my mother. In her futile attempts to curb my impulsive and often dangerous behavior, she regularly beat me with anything that came to hand, including cricket stumps and steel stair rods. Not that I blame her: it was the only way she knew how to prevent me from killing myself, apart from tying me to a chair, which she also did. For example, when in Malaysia she found out that I had been in the habit of jumping into an overflowing deep monsoon ditch and, after being swept some hundred yards or so by the turbulent water and passing through an underground pipe some thirty-odd yards long, popping out the other side, only to climb the bank, go back to the start, and do it again and again. I never considered the consequences for me if there had been a blockage in the pipe.

On another occasion when we were in Catterick shortly before leaving for Malaysia (and after I had been caught red-handed by my mother and father emerging from a perilous position beneath the wheels of a fairground ride where I had been searching for coins that had fallen out of the pockets of the people on the ride), she found out that I had been seen running across a sewage pipe that ran thirty feet off the ground, going from the back of the Regal Cinema to the kitchens of Catterick Military Hospital some hundred yards away. The game I had been playing for the amusement of myself and my friends had been to cross the pipe from the Regal side, negotiate the barbed wire on the other end, climb the bank to the kitchens and begin dumping dustbins, then wait for somebody to appear and run back across the pipe daring the kitchen staff to follow me. Needless to say, they never did.

The punch line to this story came shortly after this, when I was admitted to Catterick Military Hospital suffering from glandular fever. I was instantly recognized by a member of the kitchen staff who was serving lunch. Needless to say, my stay in the hospital was not pleasant, in more ways than one.

Someone else who was to become familiar with the hospitality of Catterick Military Hospital—though many years later and under slightly different circumstances—was a military policeman (I didn’t know he was an MP at the time). Just turned 17 and serving as a regular, I mistakenly believed that a girl apparently drinking alone at a table next to mine in the servicemen’s club was someone I had known as a child. Her boyfriend turned up and took exception to my inquisitive questioning of her, and after a brief argument, blows were exchanged outside. Thinking I had got the better of him, considering that I had just kicked him in the head with a round kick (this was 1960, by the way) and given him another whilst he was kneeling on the ground just for good luck, I foolishly turned back to talk to the girl again. However, her boyfriend was a lot tougher than I thought, and suddenly he was on my back dragging me down by the hair (which has seldom been short). Managing to gain a better position on him, I hoisted him up and dumped him over a chain link fence, where he lay on the ground cursing me.

Reflecting on the state I was in—my eye was cut, I was bleeding from my nose, my shirt jacket and trousers were torn—and then looking at him cursing me out, I clambered over the fence, mounted him and punched him into unconsciousness. I hit him so badly that in examining my shirt the next day I found the cuffs soaked in blood; the only reason things didn’t get worse for him was that I was dragged off by the military police. For some inexplicable reason, instead of arresting me they told me to fuck off. I later found out my opponent was an MP, which might have been the reason they let me go.

London 1970s

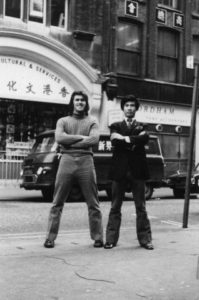

With not much building work around Reading, I decided to move to London, and after doing several casual jobs I was offered door work in the Angel by Pete Levy, a pub owner and former power-lifting champion with whom Dickie Wu and myself worked out over at Bill Stevens’ Stratford gymnasium. It was around the same time, the summer of 1971, that by chance in Chinatown I ran into Joseph Cheng of Wing Chun fame. Charismatic and with something completely new to show, he set me off on my study of Wing Chun.

Then there was an incident in the Angel which involved a prominent member of a local firm, and in order to avoid further complications, Pete told me I was no longer needed. Penniless and avoiding the landlord by shinning up and down a drain pipe to my second floor flat, I was desperate as to what to do next. Out of the blue I had a phone call from an old friend, Bob Ashing. He asked me if I would be interested in being the resident instructor of a karate club in the West End planned by one David DuBow and his wife Erika. ‘When do I start?’ was my reply.

From Joseph Cheng I’d heard that Paul Lam, another Wing Chun advocate, had recently vacated 9 Earlham Street. No sooner were the premises secured and before the paint had dried upon the walls, than I had my first private student: Tom O’Shaugnessy, a wild-eyed, dark curly-haired Irishman and a fourth dan in judo, who had brought along video equipment to record the occasion. I can never remember exactly how the conversation went, but the jist of it was he wanted to fight.

Not one to refuse, I kicked him straight in the leg and he went down (he later claimed I broke it) and then crawled off to the side. When we later reviewed the video neither of us could stop laughing. Where are you, my wild Irishman? I’m much in need of a good friend.

The incident with Tom, who was the best friend a man could ever have, gave me a feeling of déja-vu. I flashed back ten years to an Army transmitter station thirty miles outside of Nairobi, where on my very first day at the station aged 17, I was asked by an equally wild Irishman by the name of Jim Morrison if I wanted to fight. I replied I didn’t mind, and—you guessed it—I kicked him straight in the leg; and when he tried to get up and come towards me, I kicked him again. But, unlike Tom, Jim was never more than a drinking buddy.

And so, with Tom exiting stage right at a crawl, began my nine-year love affair with the 9 Earlham Street gymnasium.

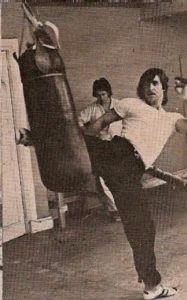

9 Earlham Street

Due to our location close to Cambridge Circus and the fact that we advertised in the American magazine Black Belt, not only did we have visitors from Chinatown and across the UK, but also from around the world: some friendly, some not. From those that were friendly I picked up new training methods and styles, whilst from those that were not I usually received a challenge to fight.

One such challenger, a Brazilian who claimed to be the champion of some unpronounceable system, challenged me whilst I was having a light workout on the bag and at the same time having an amusing conversation with Tom.

‘Later,’ I replied, but he was persistent.

Looking at Tom, I just shook my head as if to say, ‘Here we go again.’ But this time instead of squaring up to him, I had another idea. I went around opening all the windows (we were about 15 feet up on the first floor and it was winter at the time).

‘Why are you doing that?’ he asked, and even Tom looked puzzled.

‘Because when I get hold of you I am going to throw you out one of them,’ I replied.

‘Oh! I don’t want that kind of fight!’ he cried. ‘You must be crazy.’

‘That’s right,’ I replied, and he immediately went to the dressing room, got changed and departed. Tom and I carried on our conversation whilst closing the windows as if he hadn’t even existed.

The most amusing of the many challenges I ever received was when some big guy in a red crash helmet turned up in the reception area and began hurling muffled abuse at me. Whilst I couldn’t exactly understand what he was on about, his body language said it all. Suffice it to say, his helmet didn’t help him one bit.

Of the more serious fights against a variety of martial artists, none lasted very long, possibly due to the fact that I was in my prime (early thirties) and a solid 16 stone (as a result of Erika’s cooking and regularly eating out at David’s expense at some of London’s finest restaurants), superbly conditioned and explosively fast. Indeed, when we were in the States, acquaintances of David’s would often ask which football team I played for. Not to mention that I was not only a highly skilled striker on the feet, but under Tom’s guidance, my throws, takedowns and submission holds had improved considerably. In fact, a third dan international judo player once remarked he had never been thrown that hard before. Equally, because David ran an international pharmaceutical company, I was able to amass a vast library of martial arts films by way of IMS’s many offices around the world.

I would spend hours winding these films backwards and forwards on an old film editor, a process by which I was not only able to become familiar with the movement patterns, applications and training methods of many martial arts, but also to form the concept of reverse motion. This is something that Ed Parker picked up on amongst other things when he and members of the American karate team visited Earlham Street in the early Seventies.

Tom also helped broaden my viewpoint of the martial arts, not only from the perspective of the importance of groundwork, but also by providing me with the entire Wu Shu Show which had visited London in the early Seventies and which, over a number of visits, he had secretly filmed for me to analyze. Joseph Cheng, who taught Wing Chun at the club, also helped change my perception of things martial, in that it was by way of Joseph (who was from Fujian) that I first learned about the Yung Chun connection to Wing Chun and realized the possibility of a Yung Chun connection to Goju Ryu and Uechi Ryu—that was in 1971. And I purchased numerous books at Geof’s book shop in Chinatown on various systems of White Crane and the Hung systems, which Mike Chen, a student, ungrudgingly translated for me.

It was also around this time that I watched my cat Gallagher fall off a cupboard and, by twisting his head one way to face the floor and his body the other to counter the rotation, land safely on all fours. Curiosity about this event led me to begin a research into the science of human motion, or kinesiology, which later extended into sports physiology and psychology as well as combative tactics and strategies of animals and man. From a more practical perspective, with the aid of Tom and other black belt judoka at the club, I had already begun to experiment with full-contact fighting, both on the feet and on the ground, during a lunchtime session. So that by the time it was suggested to me by David that, with the prospect of expanding into Europe before us perhaps I should return to Japan to sit for my fourth dan, I was a completely different animal to the one I had been three years before. It was 1973.

Fifth Dan Grading

When I arrived at the Honbu Dojo of Yamaguchi Gogen accompanied by Miss Takahashi of IMS Tokyo Division, I didn’t expect a red carpet and fanfare, but equally I didn’t expect to be treated like a pariah by Yamaguchi Goshi, who had had a bug up his arse about me since our first meeting. During the audience with Yamaguchi Gogen I found out that I would be taking a fifth dan grading and not the fourth I had anticipated. Still seething from Goshi’s snub, instead of thanking Yamaguchi for the opportunity I warned him (much to Miss Takahashi’s embarrassment as she was acting as translator) that unlike my last trip to Japan when I had been occasionally willing to defer to those ranks above me, this time I was not. If anybody came in strong, I would come back at them stronger. Obviously angered by what I had said, Yamaguchi remained silent and the meeting was brought to a close. I thanked Miss Takahashi, who wished me good luck as we said our farewells.

A class comprised mainly of beginners, both Japanese and foreigners, was already in progress when I entered the training hall. The fifth dan instructor ordered me to join the class, to which I replied that I was going upstairs to train alone but that when his lesson was over I would be coming down to engage him in kumite. I then went upstairs and used a pillar to rehearse what I was going to do to him. On hearing the closing formalities of the lesson I ran down the stairs, burst through the door and effectively challenged him then and there. Easily closing the distance between us, I took him down to the floor and after a brief struggle whilst sitting astride him, managed to establish enough control to tap him on the forehead with my foreknuckles as if knocking on a door—and as if to say, ‘You’re dead.’ I simply didn’t have the heart to hit him (now, if he had been Goshi that would have been a completely different matter). I let him get up and he disputed the call—something about how kumite needed to remain on the feet—so I did it again. And again. Completely humiliated, he retired to the rest room where he sat with his head almost between his knees, undoubtedly reflecting on what had just happened to him.

Contrary to what the reader might assume or have heard, I’ve never hit anybody who obviously couldn’t fight—where’s the challenge in that?

On entering the dressing room I was immediately grabbed and bear-hugged by a giant Israeli who kept saying, ‘Thank you, thank you!’ Apparently this fifth dan, in typical Japanese fashion, had been taking liberties with the foreigners in his class, something which I was all too familiar with: I’d seen so many foreigners on my last trip being humiliated by some Japanese whom they could have put away in seconds if they’d had the mind to. I recall a story I heard in Japan on my first trip. This story concerned another giant Israeli, called Gideon, who after choking out a senior judoka who had apparently been making his life hell, then tied him up with his own belt and left him in the middle of the practice mat for all to see. If more foreigners training in Japan acted as Gideon did, then perhaps the Japanese martial arts would be all the healthier for it. Not that they would get an entirely clean bill of health, for there are still many foreigners who get an almost masochistic pleasure from being treated like shit or having the shit kicked out of them by some Okinawan or Japanese master, and thanking them while they pay through the nose for the privilege.

Wondering what the hell I was doing back in Japan amongst a people of whom many still deeply resented the presence of foreigners on their sacred soil, I felt like catching the next flight back to the UK and would have done so if it had not been for my obligation to David and Erika.

The grading was scheduled for the Sunday and with summer beach training scheduled for the day before, I spent the next few days revisiting places of which I’d had fonder memories. I also attended the kindergarten class for foreigners, within which Goshi repeatedly told me I was doing the forms wrong—words he would later have to eat.

Though the summer beach training on the Saturday promised to offer some light relief, the ‘play’ was far too structured for me. I did try to liven up a few games that had the potential of being great fun. The Japanese, however, simply didn’t know how to let go, which is not surprising considering that they had spent the whole of their lives being continually monitored by their superiors. Being in touch with your thoughts, emotions and sensations is one thing, but having them under the control of another person is something else. Besides, from a combative perspective I have always found it to be far more important to be in touch with the thoughts, emotions and sensations of my opponent so that I can anticipate what he might do next, whilst at the same time not allowing him to read or influence mine. From my experience, most great fighters have gregarious-type personalities and though deadly serious when it comes to fighting, are otherwise outgoing, open, and enjoy life to the full. In other words, they do not have the introspection of a Buddhist monk.

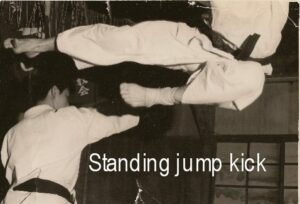

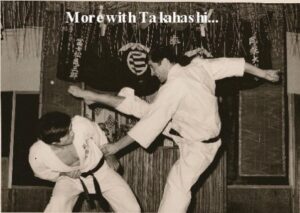

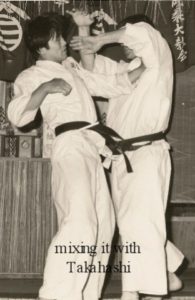

Interestingly, when we were about to get on the buses for our return to Tokyo, I was approached by Takahashi, a legend within the Goju Kai and highly regarded throughout Japan. Neither of us spoke the other’s language, so Takahashi just pointed to me and then himself and gesticulated with his hands so as to say, ‘Which one of us will be the better on the day?’ And that day was quickly approaching.

After an early dinner I returned to my hotel room, planning on an early night. But, as on many occasions before a fight I simply couldn’t sleep, and spent the entire night prowling my room like some caged animal waiting to get out. I decided that attacking would be my best strategy; it would be better to have my opponent reacting to me and capitalize on what those reactions might be, rather than the other way around. I would make my own luck, rather than wait for it to happen. I was totally committed to my course of action.

The morning of the test, I made my way to the Honbu dojo, got changed, and entered the training area. Within a short while Yamaguchi entered, to whom I bowed, followed by Goshi, to whom I didn’t, followed by somebody I didn’t recognize (but who I believe was a senior representative of Yagi Meitoku, a close friend of Yamaguchi Gogen), to whom I just nodded. Finally, the translator came in. I remembered him from my previous trip (I think he was the one I poleaxed with a single punch at my third dan grading) but he was now a third or fourth dan. But that was it. Nobody else entered the dojo. There were only five of us—where were the rest? Perhaps Yamaguchi wasn’t willing to gamble on the consequences of what I had promised to do.

And so the grading began. I was first asked to perform the Three Battle Form of Sanchin which I had been asked to demonstrate for Yamaguchi and his business acquaintances countless times before, though with Joseph Cheng’s help I had begun to modify the form so that it was more representative of Fujian boxing. I was then asked to demonstrate various other forms and their applications, which, again with Joseph’s help I had modified and for which I had learned more realistic applications. Then I was asked various questions and asked to give my views on future development of Goju Ryu, which I responded with my newly acquired knowledge of White Crane, the Hung Systems, and Wing Chun as well as of sports physiology and psychology, kinesiology, strategies, tactics and strategems. The reaction of the panel was that nobody had ever answered the questions nor spoken so eloquently on karate before.

The grading was over. After spending the entire night visualizing a fight to the finish with Takahashi, it was not the grading I had envisaged or wanted.

The one good thing to come out of the ‘grading’ was that on its completion I was approached by the ‘mystery man’ and told through the translator that my performance of kata was real karate and not the performance of a monkey. Goshi just stood there grimacing more than usual.

Reflections on the karate years

Would I have beaten Takahashi? I really don’t know, and so much water has flowed under the bridge since then that I really don’t care. It’s up to others to speculate what the outcome might have been. All I know is that I fight to win and I never quit. Indeed, I have occasionally been stunned, and often looked far worse than my opponent, but I always have managed to dig deep and call upon some hidden reserve to find a way of winning in the end even when on the brink of defeat or—as in Benghazi against an Italian armed with a knife and three Arabs—of not losing. In one incident I recall poking my head round a corner to see what was going on, only to be greeted with a rounders bat straight in the head. Not that it stopped me. I still somehow managed to break my attacker’s arm.

I suppose the beatings I received as a child have somehow conditioned me to take a beating without panicking and remain focused on what might happen next and what I have to do to deal with it. I suppose if someone were to ask me which my strongest fighting attributes are, it wouldn’t be my explosive power, speed, timing, agility and skills, etc., it would be my ability to take tremendous punishment and keep going, which when you think about it is the bottom line that usually separates winners from losers. Gary Spiers and Brian Waites both recognized this. Gary, not only a martial artist in his own right but a professional doorman for many years and a street fighter second to none, once said of me, ‘It would take an axe to stop him.’ Brian, a highly regarded martial artist, once told an extremely agitated Irishman who indicated that he fancied his chances against me while watching me teach at the Surrey Docks club in the East End to, ‘Go home and get a shot gun because you’ll need it.’ Somebody else who probably realized this was a world karate champion and successful coach, considered by many to be the best in Britain, when in the early 1970s he refused to accept my challenge to ‘come outside’ after a minor argument in a coffee shop in Belgium with other members of the B.K.A. team present.

I suppose the person who summed up best my trip to Japan was the Australian James Sumarac, who was a brown belt in 1973 but by the time of the interview with Colin Whitehead for Traditional Karate had climbed to seventh dan under Ohtsuka Tadahiko, the former senior student of Ichikawa Seisu. In this interview Sumarac not only reflected how impressed he had been with my ‘extraordinary abilities’ but how the Japanese at the Yamaguchi dojo had had no idea how to handle me.

On the flight back to the UK I couldn’t help thinking how worthless my grades and titles were. They were not, as in boxing, Muay Thai, freestyle or Greco-Roman wrestling, based upon my fighting ability, but on an apparent (in my case) commitment to a master and organization, my ability to perform the archaic movement patterns of a kata which had no basis in any reality I was aware of, my ability to engage successfully in what was nothing more than a game of hard and soft tag depending on what rules you fought under, and my ability to appear to know what I was doing and talking about in a class. Everything about karate, I decided, was so bloody subjective—and in particular the fighting. So much depended upon the judgement of a referee who often couldn’t throw or take a decent punch himself but was supposed to be able to decide if you could, or the belief that you had won the fight (even though the referee had decided you hadn’t) on the part of you, the crowd, your mother, or your girlfriend! For a third party to make a judgement call as to what is an effective shot and what isn’t is almost impossible. In fact, I’ve hit guys with shots which an observer might very well have believed would have dropped an ox, but my opponent just looked at me as if nothing had happened; whilst I’ve hit other guys with shots delivered from a matter of inches away, which an observer wouldn’t even register as a blow, and my opponent dropped as if he had been pole-axed.

Long before the plane reached Heathrow I’d already decided to put all of my efforts into encouraging the development of a full contact system of fighting in the club that was realistic, relatively safe and conclusive as to who the winner had been.

Breaking away

It didn’t take long for the Yamaguchis to agree to our plans to expand into Europe, but the catch was that a Japanese second dan, who we had previously agreed would help with the expansion, would now be in overall charge, having a final say in all matters. This proposition was unacceptable not only to me, but to David and Erika. The idea of having some wet-behind-the-ears second Dan, who in all likelihood could be beaten up by my white belts, telling me what to do was the final insult. I immediately severed my ties with the Goju Kai and relinquished my worthless grades and titles. Free from restraint, I began a program of full contact training and fighting at the renamed Earlham Street Gymnasium, the immediate result of which was that all my students, with the exception of the hardcore, began leaving the gym in droves. Thankfully they were soon to be replaced by those who only wanted to fight, and for them the fewer the rules, regulations and conventions, the better.

Because the new membership was drawn from those with boxing, Muay Thai, kickboxing, judo, wrestling, unlicensed boxing and streetfighting backgrounds, the 9 Earlham Street style began to resemble that which is known as NHB fighting today. That, however, happened thirty years ago. Not that this should be surprising: from the perspective of unarmed combat there is nothing new under the sun, except perhaps in the details of the response. Man, when faced with similar situations, has been responding in similar ways for many hundreds of thousands of years. S. Higgins got it right when he wrote, ‘Movement is inseparable from the structure supporting it and the environment defining it.’

Movement, in other words, is the individual adaptation of those inherited reflex and bequeathed behavioral patterns by which our primal ancestors were once able to adapt to changing situations within their hostile environment, and by which small children are now able to respond without instruction to situations never previously encountered. These innate patterns are uniquely expressed according to the individual’s structure and the situation, and they form the foundation of all human motor skills upon which further adaptations and refinements are made. No kinesiologist ever taught a baby how to walk! The function of a teacher, therefore, is to create realistic situations that call for a needed, ‘stimulus-oriented’ response, as it is the situation that determines the response and not the response determining the situation, which is the case in all too many martial arts. Many of the martial arts seek to manipulate the situation so that it accommodates a traditionally prescribed or favoured response.

The 9 Earlham Street style proved effective against all challengers. Indeed, I recall an amusing incident regarding one of my 9 Earlham Street students, Mark Tobin (who, if he was in his prime today would have torn the heavyweight division of the UFC and Pride apart). The incident occurred when a ‘champion’ of karate refused to put on gloves, claiming he was more effective with his bare fists. I said, ‘Well, if that’s the case, then, Mark, take off your gloves.’ On seeing the size of Mark’s hands and knuckles the champion immediately went in search of a pair of gloves. As I put Mark’s gloves back on, I whispered to him, ‘Now he’s concentrating on your hands. Kick him straight in the belly.’ Which Mark immediately did (aiming slightly lower), and the karate champion dropped like a sack of shit.

On another occasion when I was out of town, one of my students and a great fighter, the hard-as-nails at eleven stone Portuguese José Fontoura, almost single-handedly sorted out a group of Hell’s Angels who wanted a fight. When recounting the incident to me, Bob Ashing couldn’t stop laughing as he described a Hell’s Angel covered in blood crawling around the gym floor looking for his tooth, which ‘Joe’ had knocked clean out.

In the seven years that followed until the sudden death of my patron and mentor David Dubow in 1980 when the gymnasium was finally closed, neither I nor the membership had ever lost a fight against the many martial artists who visited us representing many different styles from around the world. Completely shattered by David’s death, I decided to retire from teaching and take up training horses instead of men.

Return from horse training

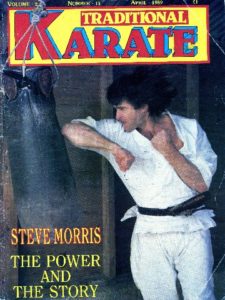

At the beginning of 1989 I received telephone calls from Terry O’Neill, a former friend, and Vince Jauncey, a former student who had made a name for himself in Muay Thai. Both wanted me to return to teaching. Indeed, the article written by Bey Logan for Traditional Karate in April, 1989 titled, ‘The Power and the Story,’ was part of a launch to mark my return.

However, the response to the article, like the seminars I conducted, was lukewarm. The martial arts establishment was still reluctant to hear what I had to say and see what I had to show, so I decided to go back to training horses, many of which over the years had kicked, bitten, butted, thrown, stamped and charged me far more effectively than any man ever had, or I suspect ever could. The late Steve Cattle in an article accompanying Bey Logan’s wrote, ‘Steve was then and is now a man ahead of his time.’ But the real truth is that I’m not so much ahead of my time but that so many martial artists are living in the past. I am simply a man of my time who has only been able to remain one step ahead of the rest of the pack by having a firm grasp of the fundamentals, being able to get past my previous assumptions of what I thought I knew, and above all remaining in touch with what is currently going on in the reality fight world.

Not that in retirement I had stopped teaching; I still had the occasional student and I was still continuing with my research into the Fujian systems and their connections with Goju ryu, Uechi ryu and the Pentchak Silak systems of Indonesia, as well as my research into sports physiology, psychology, kinesiology, etc. Indeed, it was Bruce Frantzis (whom I had known in Japan) in an interview with Simon Lailey for Traditional Karate who said that when he visited me in the early Seventies it was I who had argued for a Tiger, Crane, 5 Ancestor, Emperor Fist connection to Goju ryu and Uechi ryu, and not he. That was nearly twenty years before more media-hungry figures clamoured for the limelight.

It was also around this time that I began to receive from various sources videotape footage of NHB fighting taking place in Japan and Brazil, and which, as I said before, bore a remarkable resemblance to the 9 Earlham Street style. However, where at Earlham Street it was not easy to analyze the moves and transitions taking place within the chaotic nature of an actual fight, with the aid of the VCR, after analyzing what must have been mile after mile of videotape footage, I was able to break down NHB fighting into its fundamental skills and key moves on the feet and on the ground, as well as the strategies, tactics and strategems used by the fighters taking part in these contests against various stylistic and physical types.

What became obvious to me was that although some of the fundamental skills and key moves were unique to NHB fighting, many of the ‘moves’ had been ‘borrowed’ and adapted for NHB fighting from Western boxing, Muay Thai, freestyle and Greco-Roman wrestling, Sambo and ju-jutsu, all of which I had a knowledge of. It also followed that if the skills of NHB had been borrowed and adapted from Western boxing, etc., then so could the training methods, which I also had a knowledge of. I then began what would prove to be the most difficult part of the process: the devising, testing and refining of those exercises, drills and playfighting methods by which the fighter would become instinctively familiar with the skills, etc. of NHB and achieve that necessary mindset and level of physical conditioning required to take part in a NHB fight—something which I am still continuing to do to this day. Whilst it wasn’t immediately obvious to me when watching the NHB video footage what the fundamental skills, etc. were, it was immediately obvious that none of the successful ‘moves’ used within the NHB footage bore any resemblance by any stretch of the imagination to those of karate, tae kwon do, or kung fu. Equally, those who attempted to apply the moves of karate, etc. within NHB always came off second best—a reality I have been fully aware of since the 9 Earlham Street days.

Not that everything was entirely academic during this period. In other words, I was still having fights. Those which immediately spring to mind include the times when I disarmed a drunken tree-surgeon wielding a pitchfork in the stableyard, and when I disarmed two poachers, one with a rifle and the other with a shotgun, in the process breaking one’s wrist and the dislocating the other’s shoulder—and for being so public-spirited received an ‘unofficial’ caution from the police. My official caution was served after I gave a larger-than-normal groom the sack for mistreating two horses. I was trying to calm the horses down and had the lead ropes of each in either hand when he poked me in the chest with his forefinger and threatened to kill me, leaving me no option but to repeatedly butt him in the face until he went down. After I calmed the horses down and walked them to a paddock some distance away, I returned to the yard only to find an ambulance and police car. The ambulance was there to rush the groom off to Crawley Hospital and the police car to rush me, after I had been arrested, to the local nick, where I was charged with some kind of bodily harm. The C.P.S. never prosecuted but the police still saw it necessary to take my fingeprints and a sample of DNA, something which, quite frankly, still pisses me off. I suppose what goes around, comes around; but if that is the case, I’ve still an awful lot of karmic debts to pay off.

It was also around 1988-89 that I met Yap Leung at his martial arts shop Shaolin Way and formed an instant rapport with him. In no time Yap was enthusiastically divulging to me the intricacies of Fujian boxing. It was through Yap and his teacher, Yap Ching Hai, that I came to better understand the essential ingredients of Fujian boxing, ingredients that for one reason or another over the course of time had been removed from Goju ryu and Uechi ryu.

Putting the tiger back in its skin

It was with the idea of putting those ingredients back into Goju ryu and Uechi ryu that both Yap and I decided to hold a weekend seminar at a venue arranged by Harry Cook. Although the course seemed to have been a success, there were few follow-up phone calls. Perhaps it might have had something to do with Cook’s reluctance to engage in knocking hands with Yap again. After engaging with Yap in knocking hands on the Saturday, Cook begged off the Sunday session, which is not surprising in that both his arms looked like giant black Geordie sausages, whilst Yap’s looked perfectly normal.

What always strikes me about all too many so-called martial artists, particularly those of a karate persuasion, is that although they claim to have an open mind and give the impression they are prepared to learn from anyone who has something credible to show and say, the truth is a little different. They are only prepared to learn from those who will not contradict their particular viewpoint—which, with regard to Cook’s knowledge of knocking hands, if Cook had bothered to ask Yap how he did it, Yap would have undoubtedly done. I very much doubt when Cook has knocked hands with Higaonna Morio, who is far larger and who uses more obvious power than Yap, whose strikes are almost imperceptible, that Cook suffered anywhere near the same damage—which begs the question, how did Yap do it? Very few martial artists seem to ask this question of anybody who is truly effective. It is not a case of whether Higaonna could beat Yap in a fight, but rather, what does Yap know with regard to releasing energy that Higaonna and obviously Cook don’t, and which if Higaonna and Cook did know, they would be the better for it?

The releasing of energy in karate reminds me so much of the firing of an old cannon. Far too much more goes into the all too obvious preparations of the firing than ever comes out as an effective, accurate release. An old cannon is only really effective if you decide to stand directly in front of it and do nothing to prevent or avoid the release (which, in the case of karate, in truth is often nothing more than a splutter). Practice should be about the distilling of all those factors, both internal and external, that are essential to the rapid loading, release and re-loading of a force into a concentrated form and moment not unlike the firing of a bullet from a modern automatic firearm, rather than from some antiquated cannon. The devil might very well be in the details, but it rather depends what or whose details you are subscribing to.

By 1993 when I was invited to China by Colin Whitehead, a former student, I was closer than ever to discovering ‘the animal within’, a term that had arisen in 1971 as a result of my reading a line by Aristotle which stated, ‘The animal that moves makes its change of position by pressing against that which is beneath it.’ This apparently simple statement was to lead to over thirty years of research into how the animal, including man, organizes this ‘pressing against that which is beneath it’; the movement patterns that are the consequence of the interaction between a biological structure and its surrounding environment, the species it shares it with (including its own); and those factors that are influential upon this interaction and movement patterns: the task to be performed (the real driving force behind the organization at an unconscious level of those joint angular changes in alignment, sequence, rate, and timing of a needed response); the psychological state of mind and neuromusculoskeletal structure of the performer; those forces acting upon the body as well as generated by it; and finally the nature of the environment. Indeed, since first reading this line I have never been sure if it was I who was pursuing Aristotle’s animal, or it pursuing me.

China

As part of my trip to China an interview had been arranged with the leading boxing masters of Fuzhou City, Fujian who represented the systems of the Dragon, Lion, Tiger, Crane, Dog, Rooster, Lohan and Five Ancestor Fist. Whilst their demonstration of form was not particularly revealing (I had seen much of it before, and far better, by way of Yap Leung and his master Yap Ching-Hai), what they had to say with regards to Okinawan karate was extremely revealing—and they were in a good position to judge as they had acted as hosts on numerous occasions to those of Okinawa, Japan and the West who had travelled to Fuzhou in search of their roots. Whilst the masters didn’t dispute the historical evidence of the martial art connections between Okinawa and Fujian dating back to the early 14th Century, what they did dispute was the claim that there was any similarity, other than a superficial one, between their respective practices. The Okinawan systems, according to Li Yi Duan, then Vice Chairman of the Fuzhou Martial Arts Association, lacked in what he termed ‘essentials.’ So as to clarify this statement, I asked the masters what they thought about the way the fundamental form of Sanchin (which embodies those three internal and external essentials of Fujian Boxing) was practiced on the island of Okinawa, and they just laughed. When I asked them what they thought about the way the form is practiced in Japan they laughed even more; some of them had to wipe away the tears. Because of the age of some of the masters I didn’t dare ask them what they thought about the way the form is practiced in the West as I didn’t want to be responsible for giving any of them a coronary. However, Yap’s observation of a ‘Western master’ attempting to perform ‘shaking’ energy within a Fujian form might help: he said ‘he just wobbled.’

The masters of Fuzhou, despite the visits of some of the leading representatives of karate in the world, simply failed to acknowledge the deformed offspring named karate that had been born of a previous relationship between Fujian and Okinawa. In the same way, the masters of Okinawa, Japan and the West who had visited Fuzhou in search of their roots had failed to recognize and realize the significance of the roots of Fujian boxing from which the profusion of systems had evolved. From its introduction into the Okinawan school curriculum by Itosu Ankoh (1832-1915) at the turn of the 20th century and its later introduction into the colleges, universities, naval and military academies of Japan, Tode (or karate as it later came to be known) was altered in order to accomodate military precision marching en masse, everybody moving off at exactly the same time in exactly the same direction and in exactly the same prescribed manner to the beat of Bushido and a miliary barked-out cammand, and it has been simplified and misrepresented by every karate master and practitioner since. So that all that remains of the Tode systems of the Fujian province are the old worn-out skins and feathers into which the modern practitioners of Shin Budo have climbed. The term ‘kara’ within karate doesn’t represent the vast emptiness of ku that some wishfully imagine, but the emptiness one associates with an old rusting and battered tin can from which all the essential ingredients have been removed long ago, so that only its empty, hollow-sounding, distorted shape remains.

It was by way of this regimentation of emotions, thoughts, sensations and actions through precision marching en masse, as well as daily beatings (‘Bentatsu’) and wrapping themselves in the most superficial features of the code of the warrior by which they were willing to sacrifice their lives (‘Gyokusai’), that the youth of Japan and Okinawa were indoctrinated into those Emperor, ultranationalistic military and fascistic ideologies which were to lead to hostilities with China (1844-45), Russia (1904-5) and later during Japan’s blackest period (Showa) of her long history: the occupation of Manchuria in 1931 and the Asian Pacific War (1936-45), during which crimes against peace and humanity committed by the Japanese are amongst the most heinous ever recorded (for further reading I suggest The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang, Japanese Imperial Conspiracy by David Berganini, Hidden Horror by Yuki Tanaka and last but by no means least, Kempeitai by Raymond Lamont-Brown). For me, watching men, women and children in small groups, let alone in their hundreds (or as in Korea, in their thousands) marching en masse to an ideological beat and military barked-out command is abhorrent and has nothing to do with the martial arts in the true sense of the term, and everything to do with the indoctrination of those who engage in such practices into an ideology within which they are required to forfeit their free will and delegate the responsibility for their lives to a supreme authority, who they mistakenly believe to be a wise benefactor having their best interests at heart but who in truth is just another exploitive, self-aggrandizing piece of shit who has somehow managed to float to the top.

Anyway—back to Fuzhou and my interview with the masters. Although the morning session went well, the afternoon session was to take a turn for the worse. I spent some time literally playing with a Five Ancestor Boxer named Tao Jian during chi sau, while Cai Chu Xian, a Dog Boxer and the chief instructor of the Fuzhou Wushu Martial Arts Association, sat in the corner snarling and growling throughout the proceedings, presumably pissed off that I was making his favourite student look like a complete idiot. On the conclusion of the ‘play,’ Cai approached me, hands outstretched as if to engage hands; but instead, he rapidly changed level and came in low with vicious intent. The problem for Cai, though, was that I was used to people coming in low from my Earlham Street days, and I hip sprawled and stayed on my feet, and after neutralizing his next move, pummelled a hand inside and managed to lift and toss him clean over a coffee table and on to a couch, where I held him down until he appeared to have quietened. When I released him, however, he came at me again, this time slipping. I rebounded him back on to the couch where I held him down by his throat with one hand whilst wagging a threatening finger at one of his bulging eye balls with the other and saying, ‘No!’ as if admonishing a naughty puppy. His lips were turning purple and he was spluttering and gasping for breath, so I decided to let him go. Fortunately for him he decided to sit and stay: if he had come again (which I wish he had) he would have been in serious need of a vet!

My last recollection of Cai was of him shooting by on his scooter, his face black as thunder, with Tao sheepishly tucked in behind him. I laughed and waved goodbye, but neither of them responded. I wonder why.

Mr. Li Yi Duan, who had witnessed the incident, said that nobody had ever done that before, to which I replied, ‘More’s the pity. Maybe if they had, he would have learnt something.’ Cai, it might interest the reader to know, apart from being Head Coach, was also the student of a number of famous masters, including Wan Lai Sheng and Chen Yi-Jiu; he is the author of Fujian Ground Boxing and is seven years my junior (I was fifty at the time and still recovering from a viral infection that had reduced my normal weight of around fifteen stone to just over ten and a half) .

The consequence of this incident was that all doors in China were effectively closed to me. An interview with Wu Bin, the head of all martial arts in China, was cancelled, as was a meeting with Tony Flores’ Pakua teacher (Tony had accompanied Whitehead and me to Fuzhou). Perhaps these masters were afraid a similar incident might occur with them.

Things were obviously not going to plan, and to crown it all, whilst demonstrating knocking hands to Colin Whitehead I broke his arm. Whether Whitehead was just trying to get away from me I wasn’t quite sure, but rather than have his arm set in Beijing he left for Hong Kong almost immediately, leaving me to consider how to spend another week in Beijing. To put a positive spin on things, I decided to become just another tourist, but even that wasn’t without incident. A taxi driver who must have thought I was born yesterday had to be convinced otherwise by my holding him by his throat (a favored move) over the bonnet of his car. The incident nearly caused a riot outside of the hotel.

In the peace and quiet of my hotel room I decided that the Oriental part of my martial arts journey had come to an end. I had simply grown tired of kowtowing to masters in the hope of some good advice, when in truth their combative experiences and knowledge were nowhere near my own. Whitehead was even heard to say following the incident in Fuzhou that it should have been the masters coming to learn from me rather than the other way around.

Whilst I shall always be indebted to Yap for giving me a privileged insight into the Fujian Boxing traditions, and although they have much to offer, they are simply not for me. Attempting to clearly differentiate within the esoteric boxing forms of Fujian, let alone those of all of China, what is combative from that which has its origins in shaman, Taoist, Hindu/Buddhist magico-religious practices, mudra (i.e., the depicting of a story, emotion or action), secret society symbolism, zoomorphic display, Chi Kung gymnastics, the theatre, aesthetics or simply a fanciful display, would prove difficult enough for someone raised in the regional cultures in which these forms originated, let alone for a country boy from Penley ‘Dingles’, North Wales!

Taking on the karate establishment

Once again on a flight back to Heathrow I was reflecting on how my martial arts career was about to take a dramatic change in direction, but unlike twenty years before, all the pieces of the puzzle were now in place. The only problem I was going to have would lie in convincing the martial arts establishment that my fighting and training philosophy was a cut above the rest.

The day after my arrival home I contacted Terry O’Neill with the view of submitting a series of articles that would lay out my fighting and training philosophy. He agreed but added that as he would be in the area visiting Richard La Plante, he would drop by and see me so as to get a better idea of what I was talking about. As it turned out, O’Neill brought along La Plante, who had always wanted to meet me, and whilst most of what I showed and said was completely lost on O’Neill, it wasn’t lost on La Plante, who declared that I had peeled the onion. La Plante then put it to O’Neill that my abilities and knowledge were deserving of more attention than those of Higaonna Morio, who O’Neill seemed to be favoring at the time (there was seldom an issue of Fighting Arts International when Higaonna wasn’t on the cover). O’Neill finally, though reluctantly, agreed. The articles, however, were never published. Here’s what he had to say about me:

‘Over the 25 years of our friendship he more than any other single person has stimulated and fed my hunger for holistic knowledge of things martial,’ and in Issue No. 80 of Fighting Arts International he wrote, ‘I’ve never met anyone who could generate so much shock (as in impact rather than scary although he has done his fair share of that) over such a short range. I’m sure there are masters who can equal and even surpass Morris in this area, it’s just that I’ve yet to make their acquaintance.’ And in a postscript to a Colin Whitehead article in issue No. 85, he noted that, ‘Mr. Whitehead is correct. I am a “believer” as he puts it in Steve Morris and have been for a long time. In my 33 years of martial arts study which includes 22 years on this publication, very few people have impressed me as much as this man. His knowledge and ability are extraordinary.’

Encouraged by La Plante’s enthusiasm for what I was doing (he even wanted to make a television documentary about me), I decided to put on a gi (though reluctantly: I prefer shorts and a t-shirt) and return to the seminar circuit. I began my return with the belief that this time I was going to make a difference. However, after the first few seminars it became obvious to me that I was going to have my work cut out. The reason being that the vast majority of those attending my seminars didn’t know how to move, and most noticeably those with the highest grades. Years of practicing and perfecting Okinawan and Japanese robotics and being rewarded for it had left them without a natural movement process in their bodies. Like my father used to say, they couldn’t walk and spit at the same time. But I persisted, and my methodology seemed to be paying off. That was until two prominent karate organizations decided to warn those who attended my seminars that if they did so again, they would be effectively expelled. The result was that nobody turned up on my next seminar

It was then that I decided to never again subject myself to the humiliation of attempting to change the perception of those within karate, as well as to never again accept anyone as a student who was still practicing karate, or associate with anyone associated in any way, shape, or form with karate, even if it was going down to the local chip shop with them. In an attempt to placate me, a respected figure within karate suggested during a phone call that I should do as he did and the Japanese do: to form two groups, one comprised of those to whom I could sell the bullshit and make some money, and the other to whom I could teach the reality and establish my system and reputation. I replied, ‘The trouble with both you and the Japanese is that your reality is bullshit,’ upon which he promptly hung up.

Someone else who hung up on me was a KUGB 6th Dan who, after seeking me out and seeing what I could do and had to say, immediately wrote a letter to Terry O’Neill’s Fighting Arts International to the effect that after meeting me he had realized his training while living in Japan (where he was a member of the elite JKA Instructors Course) had been a complete waste of time. (The letter was never published—I wonder why!) Nevertheless, when I put it to him during a telephone conversation that if that was the case, shouldn’t it be I who was the technical advisor to his organization…well, you guessed it. He hung up.

Not that this individual was the only one to have said one thing and then done another. Over the twenty years I lived at Horsham I was visited by many of the senior grades and representatives of the leading Okinawan and Japanese masters in the world, and might I add, with each visit my depreciation of karate grew proportionally. Almost to a man they all effectively said the same thing: that they had learnt more under my instruction in the first thirty minutes than they had under their respective masters in the last thirty years, but the reason why they couldn’t commit themselves to my methodology the way they had committed to their masters was because they had to make a living, and if they were to have told their students that what they had been teaching for years was bullshit, their students would have been leaving their organizations in droves. One, an internationally acclaimed 6th Dan KUGB at the time (I wonder who?) put it most succinctly than the rest during one of our many telephone conversations when he said that although he didn’t believe in karate, its methods or masters, his students did and that’s how he made his living.

What was difficult for me to comprehend when I first heard this statement was how such a highly respected figure within the karate and martial arts world could stoop so low as to deceive those who attend his seminars and who hang on his every word and blindly imitate his every move, simply in order to make a living. Making a living, by the way, is something which as a trainer I have failed to do, I suppose mainly because I am too honest and pragmatic as a trainer and too competitive and ruthless as a fighter. How is it that some celluloid hero of the likes of Jean Claude Van Damme can amass a fortune or some Okinawan or Japanese master or their Western clones by way of oranizational fees, training fees, and grading fees can put in the bank hundreds of thousands of pounds a year for creating the illusion of combative effectiveness when the vast majority of those professionally engaged in reality-based fighting and training earn a pittance by comparison? The reason is that the vast majority of those engaged in the practice of the martial arts prefer the illusion of combat to the harsh reality. Perhaps I was wrong about the previously-mentioned 6th Dan deceiving those who train under him, in that it seems, being tarred with the same brush, he and his students are fully deserving of each other.

A bit of a rant

On a more personal note, with regards to the deceit practiced by those who have visited me over the years, it seems a number of them are now teaching or publicizing on the web those ‘moves,’ concepts and principles, etc. that they managed to glean from my methodology as if they are their own. Not that this will help them, in that they have failed to grasp the fundamental principles of my fighting and training system, without which they will forever be pissing in the wind.

Everybody makes mistakes in their lives, and the biggest in mine were when I put on a gi and wore it for eight years, and then after taking it off when I decided to put it back on again and reassociate myself with those who practice karate in the belief that by doing so I could convince them that their fighting and training practices were completely worthless. My only real regret about this is not that I failed to do so, but that I didn’t kick the shit out of certain individuals when I had the opportunity. But who knows? Fate being what it is, our paths might still cross and I’ll get my chance. Why, I hear some readers ask, don’t I bury the past? Well, quite frankly I’d rather bury the bastards who screwed me in one way or another than subscribe to the view of ‘live and let live’.

There are some great Japanese martial artists